Are you confident your teaching aligns with the way young children actually think? Do your preschoolers seem distracted, confused, or unengaged during lessons? Have you heard of the Piaget stages but aren’t sure how they apply to early childhood education? Are you struggling to adjust your curriculum to fit the true cognitive abilities of your students?

The Piaget stages offer a foundational understanding of how children develop cognitively throughout early childhood. By aligning teaching methods with the Piaget stages, educators can better support how young minds absorb information, process ideas, and engage with the world around them. This results in more effective learning experiences, especially during the preschool and kindergarten years when development is rapid and highly sensitive to teaching style.

In the following sections, we’ll dive deep into the Piaget stages and show you how to apply them effectively in real-world preschool and kindergarten classrooms.

Who is Jean Piaget?

Jean Piaget was a Swiss psychologist and genetic epistemologist whose work revolutionized our understanding of how children learn and develop intellectually. He proposed that children are not simply less intelligent than adults but instead think in fundamentally different ways, a concept that laid the groundwork for what we now know as the Piaget stages of cognitive development.

Born in 1896 in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, Piaget initially studied biology and philosophy, two fields that deeply influenced his later psychological theories. His early work in zoology gradually gave way to an interest in how knowledge is acquired, which led him into the emerging field of developmental psychology.

While working at the Binet Institute in Paris, which was originally focused on measuring children’s intelligence, Piaget noticed that children consistently gave wrong answers to certain questions, but those errors followed patterns based on age. This sparked his groundbreaking idea: children don’t think like adults. Instead, they move through stages of cognitive development that shape how they understand the world.

This insight became the foundation of Piaget’s theory, which emphasizes that learning is an active, constructive process. His ideas have had a lasting impact on early childhood education, helping educators better understand the stages children pass through as they grow and learn. His work remains a cornerstone of educational psychology, particularly when discussing how young minds develop in structured environments like kindergartens and preschools.

Piaget’s Stages of Development

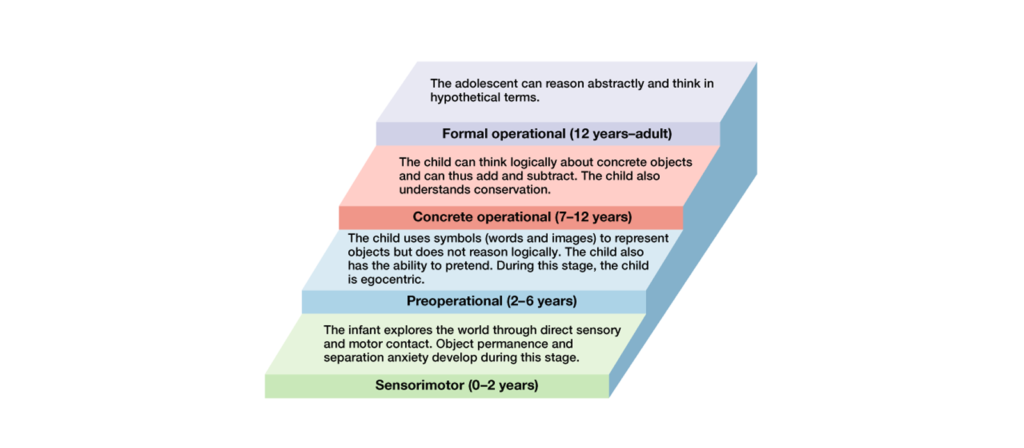

The Piaget stages of development offer a structured roadmap of how children’s cognitive abilities evolve as they grow. Rather than viewing development as a gradual accumulation of knowledge, Piaget proposed that children move through distinct cognitive stages, each characterized by a fundamentally different way of thinking. These stages help explain why a preschooler struggles with logical problem-solving while a teenager can grasp abstract algebra, since their minds are literally in different modes of operation.

The four Piaget stages of cognitive development are:

- Sensorimotor Stage (Birth to 2 years):

Infants learn through direct physical interaction with their environment. They rely on senses and motor actions to explore the world and gradually develop object permanence, the understanding that objects continue to exist even when out of sight. - Preoperational Stage (Ages 2 to 7):

Children begin to use language, symbols, and imagination. They engage in make-believe play and show egocentric thinking, meaning they have difficulty seeing things from others’ perspectives. Logical reasoning is still limited. - Concrete Operational Stage (Ages 7 to 11):

Children start thinking logically, but only about concrete, hands-on situations. They understand concepts like conservation, sequencing, and cause and effect, but still struggle with abstract or hypothetical ideas. - Formal Operational Stage (Ages 12 and up):

This final stage marks the emergence of abstract thinking. Adolescents can reason hypothetically, test theories systematically, and think about future possibilities or moral dilemmas.

In the context of early childhood education, the sensorimotor and preoperational stages are especially relevant. Understanding these stages allows educators and parents to design age-appropriate learning experiences. For example, expecting logical reasoning from a 4-year-old typically leads to frustration for both the child and the teacher. But when learning activities match the child’s cognitive level, engagement and comprehension soar.

By identifying where a child stands within the Piaget stages, educators can better plan instruction, select materials, and assess learning outcomes. This stage-based approach is now widely used in curriculum design, especially in preschools, kindergartens, and Montessori settings.

Sensorimotor Stage: Birth to 2 Years

The sensorimotor stage is the first of the Piaget stages, spanning from birth to approximately 24 months. During this period, infants progress from simple reflexive responses to intentional, goal-directed actions. Cognition begins not with words, but through sensory exploration and physical activity such as seeing, touching, tasting, grasping, and moving.

Infants at this stage live “in the moment,” with no internal mental representations of the world. However, by the end of the stage, they develop symbolic thinking, object permanence, and the foundational structures for language and problem-solving. In Piaget’s view, this stage is when the mind begins to form.

Key Characteristics in the Sensorimotor Stage

Learning through senses and actions: Infants explore the world physically before they can think symbolically.

Development of schemas: Babies form mental structures through repeated interactions, slowly understanding how things behave.

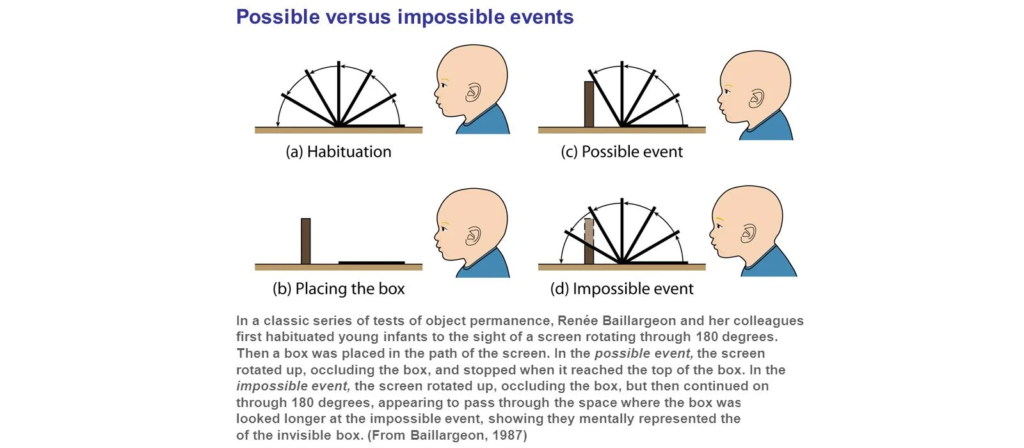

Object permanence: Around 8 months, infants begin to grasp that objects still exist even when out of sight, a major leap in mental representation.

Emergence of symbolic function: Toward the end of this stage, children start to use one object to represent another and begin to use language.

自己認識: Infants gradually recognize themselves as distinct from others.

Six Substages of the Sensorimotor Stage

Reflexive Stage (0–2 months)

During the first substage, known as the reflexive stage, infants function almost entirely on innate reflexes. Actions such as sucking, grasping, and blinking occur automatically and are not yet under the baby’s conscious control. At this point, cognition has not yet taken shape; instead, these reflexes serve as the initial mechanisms through which infants begin interacting with their environment. Though these movements may seem basic, they are vital in establishing early sensory-motor connections that will support future learning.

Primary Circular Reactions (2–4 months)

As infants enter the primary circular reactions substage, they begin to repeat actions that bring them comfort or pleasure, but still primarily focus on their own bodies. For instance, a baby might discover thumb-sucking accidentally and continue to do it repeatedly because it feels good. The key development here is repetition. Although the behavior is not yet goal-directed, it marks the infant’s first recognition that actions can be self-initiated and repeated to produce desired sensations. This self-discovery begins to build the foundational concept of control over one’s own body.

Secondary Circular Reactions (4–8 months)

The secondary circular reactions substage introduces a dramatic shift. At this stage, babies begin interacting intentionally with objects and people in the external world. They repeat actions not just for internal satisfaction but to elicit responses from their environment. For example, they may shake a rattle to hear the sound or kick a hanging mobile repeatedly to watch it move. These behaviors reflect an emerging understanding of cause and effect beyond the self. Cognition is expanding outward as infants realize they can influence objects around them through their actions.

Coordination of Secondary Circular Reactions (8–12 months)

Progressing into the coordination of secondary circular reactions substage, infants become more deliberate and goal-oriented in their actions. They can now coordinate multiple actions to achieve a specific outcome. For instance, a baby might push a cushion aside to retrieve a hidden toy, indicating that the child can plan ahead and combine steps toward a goal. This substage also marks the early appearance of object permanence, the realization that objects continue to exist even when they’re out of sight. This marks one of the major intellectual breakthroughs in the Piaget stages, as it requires forming a mental representation of something not immediately present.

Tertiary Circular Reactions (12–18 months)

In the tertiary circular reactions substage, infants begin to experiment intentionally with variations of their actions to see new results. Rather than repeating the same action, they try different behaviors to learn how outcomes change. For example, a toddler may drop a toy from different heights or bang it against various surfaces to see what happens. This substage reflects curiosity and problem-solving through trial and error, the early roots of scientific thinking. Cognitively, the child is testing hypotheses through action, and the world becomes a place of experimentation.

Mental Representation (18–24 months)

Finally, the mental representation substage marks the most significant leap in this stage. At this point, children can form internal images of objects and events. They are now capable of deferred imitation, observing an action and reproducing it later, and symbolic play, such as pretending a block is a phone. These abilities indicate the emergence of symbolic thinking, a key trait of the upcoming preoperational stage in the broader Piaget stages of cognitive development. Children also begin using simple language, not just as sound, but as a way to represent ideas and objects, reflecting a growing ability to mentally process and communicate about the world.

By the end of the sensorimotor stage, children are no longer passive observers of the world. They begin to understand that objects exist independently, actions have consequences, and symbols can stand for real things. This transformation marks the emergence of true cognition, a shift from reactive behavior to intentional, representational thought. These achievements form the mental foundation for the next Piaget stage: the preoperational stage, where imagination, language, and symbolic play take center stage in a child’s learning journey.

How to Support Children in the Sensorimotor Stage

In Piaget’s theory, the sensorimotor stage highlights how infants build knowledge through their senses and actions. To support this process, caregivers and educators should provide safe, stimulating opportunities that match Piaget’s stages of cognitive development.

Practical strategies include offering toys and activities that engage multiple senses. Rattles, textured balls, and stacking cups encourage infants to practice grasping, shaking, and problem-solving. Games such as peek-a-boo or hiding and revealing objects reinforce the concept of object permanence, one of the most important milestones of this stage. Providing mirrors or encouraging imitation also fosters early self-awareness and symbolic play.

For teachers applying Piaget’s theory in early childhood education, this stage is not about formal instruction but about designing environments rich in sensory experiences. Activities like water play, crawling through tunnels, and exploring Piaget’s theory and preschool teaching, ensuring that infants are not just entertained but are laying the foundation for deeper learning in the preoperational stage and beyond.

学習意欲を高める空間をデザインする準備はできていますか? 教室のニーズに合わせてカスタマイズされた家具ソリューションを作成するには、当社にご相談ください。

Preoperational Stage: Ages 2 to 7

The preoperational stage, which spans from approximately age 2 to 7, is the second major phase in the Piaget stages of cognitive development. During this period, children undergo significant mental expansion as they begin to think symbolically and use language to communicate, express, and imagine. However, their reasoning is still dominated by perception and intuition rather than logic.

This is a time of imaginative play, vivid storytelling, and emerging vocabulary. Children in the preoperational stage are no longer limited to the “here and now” like in the sensorimotor period; instead, they start thinking about people, objects, and events that are not physically present. They can draw what they remember, retell past experiences, or pretend a banana is a phone. Despite this leap, logical operations, such as cause-and-effect reasoning and understanding conservation, remain beyond their grasp.

Key Characteristics in the Preoperational Stage

Symbolic thinking develops rapidly: Children begin using symbols, such as words, drawings, and gestures, to represent objects and experiences. This is a core marker of the preoperational stage in Piaget’s theory.

Language acquisition accelerates: Vocabulary grows quickly, and children learn to form sentences, tell stories, and ask questions to explore the world around them.

Egocentric thinking dominates: Children believe that everyone sees, thinks, and feels exactly as they do. They find it difficult to understand different perspectives.

Centration influences perception: Centration influences perception: Children focus on one aspect of a situation or object at a time, for example, noticing height but ignoring width when comparing containers.

Lack of conservation: They do not yet grasp that quantity stays the same even when the shape or arrangement changes (e.g., same water volume in a tall vs. wide glass).

Animism and magical thinking appear: Children often attribute life-like qualities to non-living objects, such as saying, “My doll is sad” or “The moon is following me.”

Pretend play becomes complex: Children use their imagination to act out roles and stories, which helps them process experiences and build social understanding.

Intuitive reasoning begins to form: Children start asking “why” questions and give explanations, even if those explanations are based more on how things look than on how they work logically.

Two Substages of the Preoperational Stage

According to Piaget’s theory, the preoperational stage can be further divided into two distinct substages: the symbolic function substage and the intuitive thought substage. Each represents a unique phase in how children begin to represent and reason about their world.

Symbolic Function Substage (Ages 2–4)

In the symbolic function substage, children develop the ability to mentally represent objects that are not physically present. This allows them to engage in symbolic play, use language more expressively, and begin drawing pictures that stand for real-world items. A child might pretend a stick is a sword or imitate a parent cooking dinner using toy food. However, during this substage, thinking is still heavily driven by perception. If something looks taller, it must be “more.” If something is closer, it must be “bigger.” These intuitive judgments form the basis for understanding the world, but they are not yet based on logic.

Intuitive Thought Substage (Ages 4–7)

In the intuitive thought substage, children begin to ask many “why” and “how” questions as they explore their surroundings. Their thinking is no longer purely perceptual, and they begin to use early reasoning skills, though these are still immature. For example, a child may reason that plants grow because they’re “happy,” or that the sun sets so it can “go to sleep.” This kind of intuitive thinking is typical: it’s creative, imaginative, and often wildly inaccurate. Children begin to form guesses about how things work, but they do not yet understand abstract concepts or logical sequences.

By the end of the preoperational stage, children are equipped with a rich imagination, a growing vocabulary, and the emerging ability to use symbols in play and communication. Though their thinking is still dominated by perception and intuition, they are beginning to explore reasoning and ask meaningful questions about the world. These developments form the foundation for the next step in the Piaget stages of cognitive development, the concrete operational stage, where logic, structure, and mental operations begin to take shape.

How to Support Children in the Preoperational Stage

In Piaget’s theory, the preoperational stage is when children begin to think symbolically and expand their use of language, but their reasoning remains intuitive and egocentric. To support children at this level of the Piaget stages of cognitive development, adults should design activities that encourage imagination, dialogue, and early problem-solving without demanding abstract logic.

Practical strategies include encouraging pretend play, role-playing, and storytelling. Providing dress-up clothes, puppets, or toy kitchens allows children to act out real-life situations, helping them develop social understanding and creativity. Simple drawing or art projects also give children opportunities to represent ideas symbolically. Conservation experiments with cups of water, playdough shapes, or blocks can gently introduce early logical concepts, even if children are not yet ready to master them.

For educators applying Piaget’s theory in early childhood education, the focus should be on open-ended play and guided questioning. Asking children “why” and “what if” helps them articulate their reasoning and practice early perspective-taking. In line with Piaget’s theory and preschool teaching, the goal is not to rush children into formal logic but to nurture curiosity and provide tools for expressing thoughts, laying the groundwork for the concrete operational stage.

Concrete Operational Stage: Ages 7 to 11

The concrete operational stage, spanning ages 7 to 11, is the third phase in the Piaget stages of cognitive development. In this period, children begin to develop the ability to think logically about concrete, tangible events. Unlike earlier stages, their reasoning is no longer dominated by appearance or intuition, and they can now perform mental operations, understand rules, and think more systematically. This marks a significant shift in Piaget’s theory, as it’s the point where children begin moving from “what things look like” to “how things work.”

Children in the concrete operational stage can classify objects, understand relationships, and follow logical sequences. Their thinking becomes more organized and rule-based. For educators and caregivers, this is the time when children begin to truly grasp mathematical concepts, time, measurement, and structured problem-solving.

Key Characteristics in the Concrete Operational Stage

Logical thinking about concrete situations: Children develop the ability to apply logical rules to real-world situations, such as solving problems related to volume, weight, or time.

Conservation is understood: They now recognize that quantity remains the same even when its shape or appearance changes, whether it’s water in a different glass or clay molded into a new form.

Decentration emerges: Children can consider multiple aspects of a situation at once, such as both the height and width of a container, leading to more accurate judgments.

Reversibility is achieved: They can mentally reverse a sequence of events or changes. For example, they know that 3 + 2 = 5 also means 5 – 2 = 3.

Classification and seriation skills strengthen: Children can sort objects based on multiple features (like size and color) and order them along a dimension, such as from smallest to largest.

Perspective-taking improves: Egocentrism continues to decline, and children become better at understanding other people’s viewpoints and feelings.

By the end of the concrete operational stage, children are equipped with the tools of logic and systematic thinking, preparing them to enter the next phase of Piaget’s theory, where abstract reasoning begins to emerge.

How to Support Children in the Concrete Operational Stage

In Piaget’s theory, the concrete operational stage is when children start to apply logical thinking to real-life situations. They can now handle conservation tasks, classification, and reversibility, but their reasoning is still tied to concrete objects and experiences. To support children in this phase of the Piaget stages of cognitive development, educators and parents should provide hands-on, structured activities that make abstract concepts visible and tangible.

Practical strategies include using manipulatives in mathematics, such as blocks, beads, or fraction tiles, to help children visualize operations. Science experiments where children measure, classify, or test variables reinforce their ability to apply logic systematically. Board games with rules, such as “Connect Four” or card games, build logical reasoning and encourage fair play. Group projects, like sorting objects or designing a simple experiment, foster cooperation and perspective-taking.

For teachers applying Piaget’s theory in early childhood education, the focus should be on encouraging exploration through real-world problem-solving. Story problems in math, time-based activities, and structured classification exercises make concepts meaningful. In line with Piaget’s theory and preschool teaching, learning should remain active and interactive, ensuring that children connect logic with everyday experiences. This approach lays the foundation for the abstract reasoning that emerges in the formal operational stage.

学習意欲を高める空間をデザインする準備はできていますか? 教室のニーズに合わせてカスタマイズされた家具ソリューションを作成するには、当社にご相談ください。

Formal Operational Stage: Ages 12 and Up

The formal operational stage marks the final phase in the Piaget stages of cognitive development. Beginning around age 12 and continuing into adulthood, this stage is defined by the ability to think abstractly, reason hypothetically, and mentally manipulate ideas that are not tied to physical objects or direct experience. It represents the full maturation of cognitive function as described in Piaget’s theory.

While earlier stages are grounded in concrete experiences and sensory input, the formal operational stage allows individuals to explore possibilities, test assumptions, and engage in scientific and philosophical thinking. This is the stage where adolescents begin to form complex opinions, consider multiple perspectives, and question rules, systems, and societal structures.

Key Characteristics in the Formal Operational Stage

Abstract reasoning develops: Teenagers begin thinking about concepts like freedom, justice, ethics, and hypothetical scenarios without needing physical examples.

Hypothetical-deductive reasoning emerges: They can form a hypothesis, systematically test it, and draw conclusions, which is a core element of scientific thought.

Metacognition strengthens: Adolescents become more aware of their own thinking processes. They can reflect on how they learn, think about their mistakes, and revise their strategies.

Systematic problem-solving skills appear: Rather than relying on trial and error, students approach problems with structured methods and logic.

Moral and philosophical reasoning expands: Teens can now consider abstract moral dilemmas, future consequences, and complex human relationships.

How to Support Children in the Formal Operational Stage

In Piaget’s theory, the formal operational stage marks the ability to think abstractly, reason hypothetically, and handle complex problem-solving. This final phase of the Piaget stages of cognitive development usually begins around age 12 and extends into adulthood. While children can now imagine possibilities beyond the concrete, they still need structured opportunities to practice applying logic to abstract situations.

Practical strategies include introducing debates, ethical dilemmas, and open-ended questions that encourage hypothetical reasoning. Activities such as science experiments requiring hypothesis testing, strategy-based board games, or designing group projects help children refine logical thinking. Creative writing tasks or simulations, such as mock trials or role-playing social issues, promote abstract reasoning and perspective-taking.

For educators applying Piaget’s theory in early childhood education, this stage highlights the importance of encouraging critical thinking and reflection. Teachers can ask students to explain their reasoning, compare multiple solutions, or consider alternative perspectives. In line with Piaget’s theory and preschool teaching, the goal is to strengthen abstract thought while still connecting ideas back to real-life experiences. By guiding children to think beyond what is visible, educators prepare them to tackle the challenges of adolescence and adulthood with intellectual flexibility.

5 Important Concepts in Piaget’s Work

Beyond the four Piaget stages of cognitive development, Jean Piaget also introduced several key concepts that explain how children move from one stage to the next. These ideas form the backbone of Piaget’s theory, and they remain highly influential in modern education and developmental psychology. For teachers and caregivers, understanding these concepts is just as important as knowing the stages themselves, because they reveal the processes that drive learning and growth.

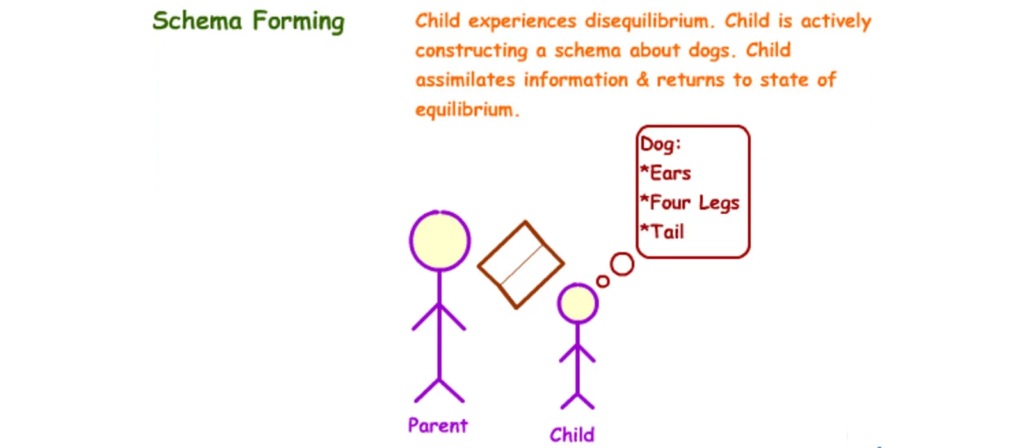

1. Schemas (Mental Structures)

At the heart of Piaget’s theory is the idea of schemas, mental structures or frameworks that help children organize knowledge and experiences. A schema is like a mental “file” for understanding the world. For example, a child might have a schema for “dog” that includes four legs, fur, and barking. As the child encounters new animals, they adjust or expand this schema. Schemas are constantly evolving as children interact with their environment, making them the foundation of all learning in the Piaget stages.

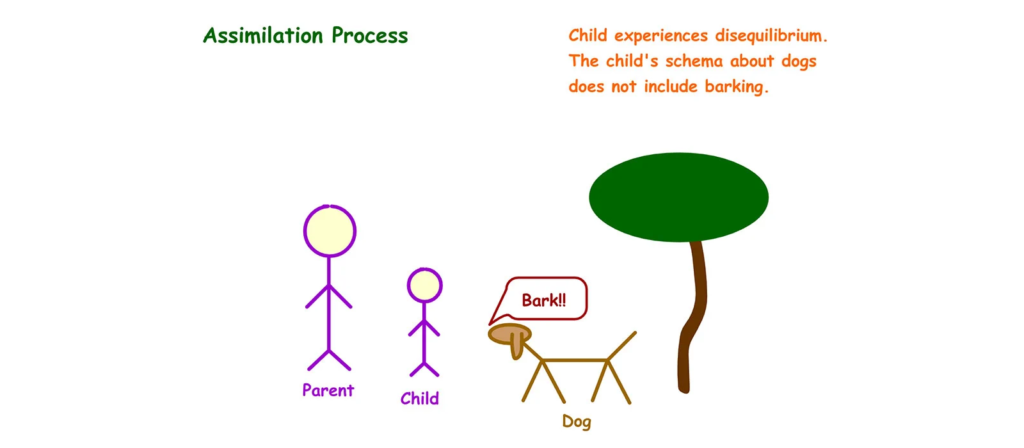

2. Assimilation

Assimilation occurs when a child interprets new experiences in terms of existing schemas. For instance, when a child first sees a large, unfamiliar animal like a wolf, they might still call it a “dog,” because their schema for “dog” is based on four legs, fur, and barking. This process shows how children fit new information into what they already know, even if their classification is not entirely accurate. Assimilation helps maintain continuity in thinking across the Piaget stages of cognitive development.

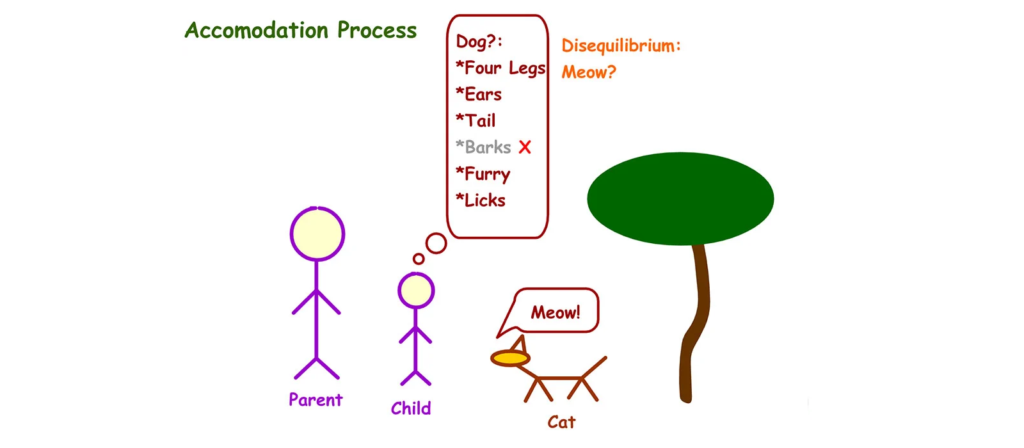

3. Accommodation

Accommodation happens when existing schemas are no longer sufficient and must be modified. Returning to the dog example, imagine a child who first calls every four-legged furry animal a “dog.” When they encounter a cat, they might still label it as a dog at first. But after noticing that cats meow instead of barking, and often behave differently, they realize cats and dogs are distinct animals. They adjust their schema, now separating “dog” from “cat.” This restructuring process is critical in Piaget’s theory because it allows children to refine their understanding and progress to more logical, accurate ways of thinking. Without accommodation, learning would stagnate.

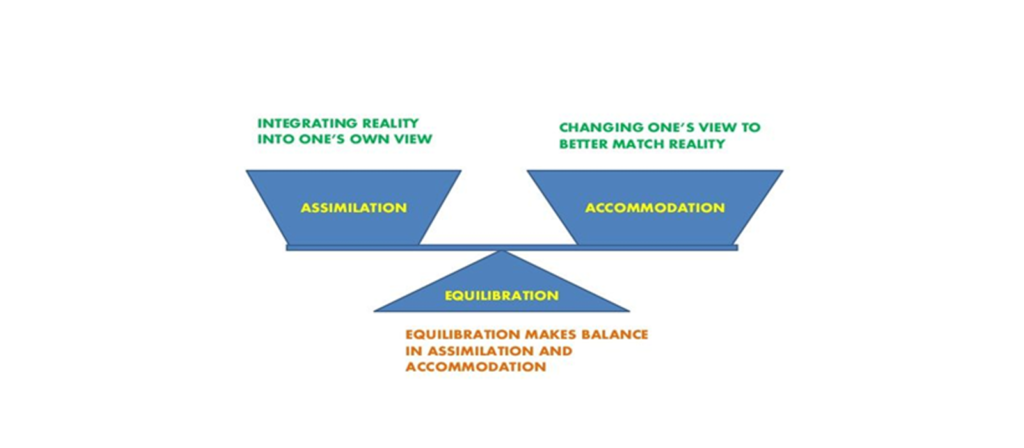

4. Equilibration

Equilibration is the balance between assimilation and accommodation, the driving force of cognitive development in Piaget’s theory. When children encounter something that doesn’t fit their current schemas, they experience cognitive disequilibrium. By accommodating and adjusting their schemas, they return to equilibrium with a new, more sophisticated understanding. Equilibration is what pushes children from one stage of development to the next, making it central to the movement through the Piaget stages.

5. Object Permanence and Symbolic Function

Among the most famous achievements described in Piaget’s theory are object permanence (the understanding that objects continue to exist even when unseen) and symbolic function (the ability to use symbols such as language and pretend play). These concepts mark critical turning points in the Piaget stages of cognitive development. They explain how children move from living “in the moment” during the sensorimotor stage to representing the world mentally in the preoperational stage. Both are essential for learning, communication, and imagination.

These five ideas (schemas, assimilation, accommodation, equilibration, and symbolic function) form the core of Piaget’s theory. They explain how children progress through the Piaget stages of cognitive development and guide how we apply Piaget’s theory in early childhood education and preschool teaching.

Application of Piaget’s Theory in Early Childhood Education Settings

The true strength of the Piaget stages is that they not only describe how children think but also show us how to teach them effectively. Piaget’s theory tells us that children are not passive learners; they build knowledge by exploring, playing, and interacting. In early childhood education, this means classrooms should focus less on memorization and more on creating environments where children learn by doing, questioning, and experimenting.

Using Play to Support Cognitive Development

Play is the most natural way to apply Piaget’s theory and preschool teaching, and Piaget himself described how children’s play evolves alongside their cognitive growth. In his view, there are four main types of play that mirror the Piaget stages of cognitive development: functional play, symbolic or pretend play, constructive play、 そして games with rules. Each of these play types connects directly to the developmental stages outlined in Piaget’s theory.

- Sensorimotor stage (0–2 years): Babies learn through their senses and movement. Activities like peek-a-boo, rattles, water play, or crawling through tunnels help develop object permanence and motor coordination.

- Preoperational stage (2–7 years): Children enjoy 劇的な遊び. Pretending a block is a car, acting out a shopkeeper role, or drawing pictures helps them practice imagination, expand vocabulary, and build social understanding.

- Concrete operational stage (7–11 years): At this point, logical thinking is growing. Board games with rules, puzzles, and sorting tasks strengthen reasoning. Cooperative play teaches fairness and turn-taking.

- Formal operational stage (12+ years): Older children benefit from games that involve strategy, hypothesis testing, or debate. Science experiments, mock trials, or abstract discussions push them toward abstract reasoning.

By matching play to developmental stages, teachers make learning both enjoyable and effective, exactly in line with Piaget’s theory in early childhood education.

Creating a Constructivist Learning Environment

Piaget’s theory is rooted in constructivism, the idea that children actively construct knowledge. In practice, this means classrooms should provide hands-on, open-ended activities rather than worksheets or rote drills.

For example, instead of just reading about insects, children could observe them in nature, touch them carefully, and then draw what they see. A math lesson might start with counting real objects like blocks or fruit before moving to symbols on paper. These experiences allow children to make connections, experiment, and learn through trial and error.

In early childhood education, this kind of environment helps children see learning as an exciting process, not a passive task. Teachers act as guides, setting up challenges and asking questions rather than simply delivering answers.

Assessing Developmental Readiness

The Piaget stages of cognitive development remind us that children are ready for different types of learning at different times. A preschooler who has not yet developed conservation will not understand that the same amount of water can look “different” in two containers. Pushing such tasks too early only causes frustration.

Educators should instead look for signs of readiness, such as a child’s ability to classify objects, understand rules, or use abstract language, before introducing more advanced tasks. This approach respects the child’s stage of development and builds confidence through achievable challenges.

This is one of the most practical ways to apply Piaget’s theory: always ask, “Is this task appropriate for where the child is now?”

Encouraging Social Interaction

Piaget’s theory and preschool teaching emphasize that children learn not just by exploring alone but by interacting with others. Group activities, cooperative games, and role play all help children see different perspectives.

In the preoperational stage, children might act out social roles, such as running a pretend grocery store together. In the concrete operational stage, rule-based games like “Simon Says” or “Musical Chairs” encourage cooperation and fairness. Older children benefit from discussions about moral dilemmas or classroom debates, where they must consider viewpoints beyond their own.

These interactions help reduce egocentrism and foster social reasoning, both vital skills in education and life.

Providing Opportunities for Reflection

As children reach the formal operational stage, they develop metacognition, the ability to think about their own thinking. Educators can nurture this by asking reflective questions:

- “How did you figure that out?”

- “What could you try differently next time?”

- “Why do you think that happened?”

This practice encourages children to evaluate their reasoning and consider alternatives. Over time, it builds critical thinking and decision-making skills, showing the depth of what Piaget’s theory can bring into modern classrooms.

Recognizing Individual Differences

Finally, while the Piaget stages provide a useful roadmap, every child develops at their own pace. Some may reach certain milestones earlier, while others need more time. For educators, this means flexibility is essential.

In early childhood education, teachers should use Piaget’s theory as a guide, not a rigid checklist. Activities should be adaptable, offering multiple entry points so that children with different abilities can all engage meaningfully. When children are given space to learn at their own speed, they are more confident, curious, and motivated.

学習意欲を高める空間をデザインする準備はできていますか? 教室のニーズに合わせてカスタマイズされた家具ソリューションを作成するには、当社にご相談ください。

Benefits of Piaget’s Stages of Development

Understanding the Piaget stages of cognitive development provides educators and parents with more than just a theory; it offers a roadmap for guiding children’s learning in real-world contexts. By applying Piaget’s theory in preschool and early education, we can better match teaching strategies to the way children naturally grow and think.

Clarity on Developmental Milestones

One of the greatest benefits of the Piaget stages is that they outline clear milestones in thinking, from object permanence in infancy to abstract reasoning in adolescence. Teachers and caregivers gain a practical framework to evaluate what children are ready to learn. Instead of expecting a preschooler to solve problems they cannot yet grasp, educators can design stage-appropriate tasks that build confidence and success.

This makes Piaget’s theory and preschool teaching more effective because lessons align with actual developmental abilities.

Improved Teaching Strategies

Applying Piaget’s theory in early childhood education shifts the focus away from rote memorization toward exploration, hands-on learning, and discovery. A teacher who understands the Piaget stages will provide sensory play for toddlers, imaginative role-play for preschoolers, and logical problem-solving for older children.

This tailored approach keeps children engaged, helps them retain knowledge, and encourages curiosity. In essence, it turns learning into a natural extension of play and exploration.

Support for Social and Emotional Growth

The Piaget stages of cognitive development also highlight the role of social interaction. As children move from egocentric thinking toward perspective-taking, group activities and cooperative games become powerful tools for teaching empathy, fairness, and teamwork.

Educators who apply Piaget’s theory not only strengthen intellectual growth but also help children build essential social skills. These social-emotional benefits are just as important as academic achievement in early education.

Flexibility and Individualization

Finally, understanding the Piaget stages allows teachers to adapt to individual differences. While Piaget outlined universal patterns, not all children move through the stages at the same pace. Using this framework, educators can identify children who may need extra support or those ready for more advanced challenges.

This flexibility makes Piaget’s theory and preschool teaching practical in diverse classrooms, ensuring that each child is met where they are.

Criticisms Of Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

While the Piaget stages of cognitive development have shaped modern education, researchers and educators have also pointed out several limitations. Understanding these criticisms allows us to apply Piaget’s theory more thoughtfully in early childhood education and preschool teaching.

Underestimation of Children’s Abilities

One of the most common criticisms is that Piaget underestimated children’s cognitive skills. Later studies found that even infants may show signs of object permanence earlier than Piaget suggested. Similarly, some preschoolers can demonstrate logical reasoning in simple tasks if the questions are framed clearly.

This means that while the Piaget stages are useful as a guide, children may develop certain skills earlier than the theory predicts. Educators should therefore avoid treating the stages as rigid timelines.

Overemphasis on Stages

Critics argue that Piaget’s theory presents development as a series of distinct steps, but in reality, growth can be more continuous and overlapping. For example, a child may display preoperational characteristics in one task but concrete operational reasoning in another.

In the context of Piaget’s theory in early childhood education, this highlights the need for flexibility. Teachers should observe individual children carefully rather than assuming all abilities fit neatly within one stage.

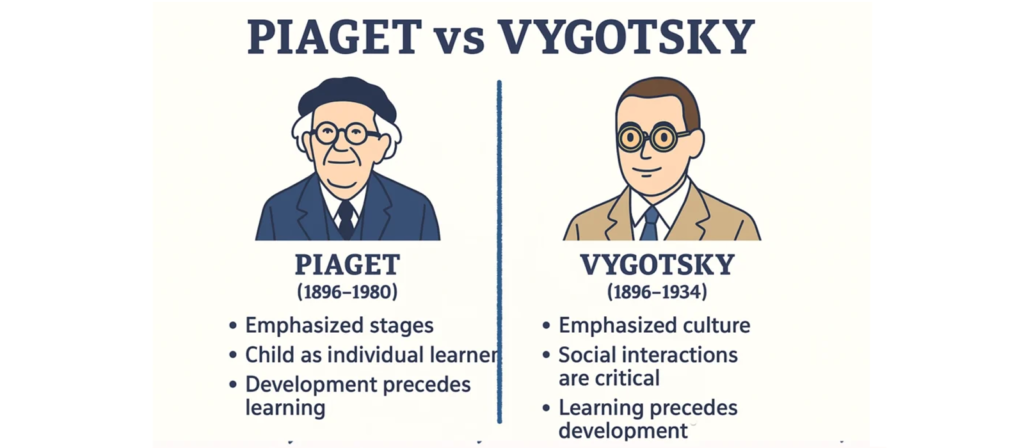

Limited Consideration of Culture and Social Factors

Another criticism is that Piaget’s theory focused heavily on individual exploration while giving less attention to culture, language, and social interaction. Researchers like Vygotsky later emphasized the importance of social context in learning.

For preschool teaching, this means educators must balance Piaget’s insights with strategies that emphasize collaboration, communication, and cultural influences on development.

Methodological Concerns

Some scholars also question the methods Piaget used, noting that his experiments were often small-scale, based on his own children, and sometimes lacked standardization. While his observations were groundbreaking, they may not fully represent all children’s experiences.

This does not diminish the value of the Piaget stages, but it reminds educators to use the theory as a flexible framework, not a strict rulebook.

Piaget vs. Vygotsky: Key Differences and Similarities in Cognitive Development Theories

Both Piaget’s theory and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory shaped how we understand learning in childhood. While their differences are often highlighted, they also share important common ground. Below, we compare both the contrasts and the similarities, showing how they complement each other in early childhood education and preschool teaching.

Key Differences

| 側面 | Piaget’s Theory | Vygotsky’s Theory |

|---|---|---|

| View of Development | Cognitive growth occurs in universal Piaget stages (sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, formal operational). | Development is continuous and shaped by culture, context, and interaction. |

| Learning Process | Children are “little scientists,” constructing knowledge through individual exploration. | Children learn primarily through social interaction and collaboration with others. |

| Role of Language | Language develops as part of symbolic thinking during the Piaget stages of cognitive development. | Language is the primary tool of thought, central to learning and reasoning. |

| 教師の役割 | The teacher acts as a guide, offering scaffolding and support within the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). | Teacher acts as a guide, offering scaffolding and support within the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). |

| Educational Implications | Focus on hands-on activities, discovery learning, and stage-appropriate tasks. | Focus on guided practice, peer collaboration, and culturally meaningful instruction. |

Key Similarities

| 側面 | Piaget and Vygotsky |

|---|---|

| Constructivist Approach | Both see children as active learners who build knowledge through interaction with their environment. |

| Importance of Play | Both emphasize play as essential for learning. For Piaget, play reflects assimilation; for Vygotsky, it supports role-taking and social growth. |

| Role of Interaction | Both agree that interaction — with objects (Piaget) or with people (Vygotsky) — drives cognitive development. |

| Educational Value | Both theories deeply influence early childhood education, encouraging teachers to move beyond rote learning toward exploration, dialogue, and problem-solving. |

Frequently Asked Questions about Piaget Stages

What are the four Piaget stages?

The Piaget stages of cognitive development include four phases:

- Sensorimotor stage (0–2 years): Infants explore the world through senses and actions, eventually developing object permanence.

- Preoperational stage (2–7 years): Children begin symbolic thinking and use language and imagination, though reasoning is still intuitive.

- Concrete operational stage (7–11 years): Children use logical thinking and understand conservation, but still rely on concrete objects.

- Formal operational stage (12+ years): Adolescents develop abstract reasoning, hypothetical thinking, and higher-order problem-solving.

How does Piaget’s theory explain children’s learning?

Piaget’s theory sees children as active “constructors of knowledge.” They learn by interacting with their environment, experimenting, and playing. Learning happens through assimilation (fitting new information into existing schemas) and accommodation (adjusting schemas when old ones no longer work). Together, these processes drive growth across the Piaget stages.

What factors influence learning according to Piaget?

In Piaget’s theory and preschool teaching, children’s learning is shaped by several key factors:

- Maturation: Biological and neurological development sets the foundation for new abilities.

- Experience: Interaction with the physical environment provides essential learning opportunities.

- Social interaction: Conversations and collaboration with peers, teachers, and parents challenge thinking.

- Equilibration: The internal process of balancing new information with existing knowledge to restore cognitive stability.

What is the main significance of Piaget’s stages?

The Piaget stages of cognitive development provide a roadmap for educators and parents. They show that:

In early childhood education, applying Piaget’s theory ensures lessons nurture curiosity, language, logic, and social growth at the right time.

Children think in qualitatively different ways at different ages.

Teaching should match the child’s developmental level rather than push abstract ideas too early.

Is Piaget’s theory still relevant today?

Yes. Even with its criticisms, the Piaget stages of cognitive development remain a cornerstone in child psychology and preschool teaching. When used flexibly, they continue to guide educators in creating learning environments that foster curiosity, problem-solving, and social growth.

結論

Understanding the Piaget stages of cognitive development provides a clear framework for how children grow from sensory exploration to symbolic thinking, logical reasoning, and eventually abstract problem-solving. By applying Piaget’s theory in classrooms and homes, educators and parents can design experiences that match developmental readiness, promote curiosity, and encourage both independent exploration and social learning.

In practice, Piaget’s theory in early childhood education is not just a theoretical guide but a practical tool for shaping environments that nurture growth. When teachers use insights from Piaget’s theory and preschool teaching, children benefit from activities and surroundings that align with their stage of development. Quality educational settings often depend on supportive resources, and this is where providers of child-centered kindergarten furniture, such as ウェストショア家具, naturally complement these principles by creating spaces that allow Piaget’s ideas to flourish.